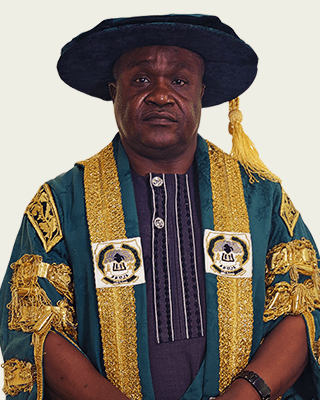

Professor Michael Umale Adikwu is a distinguished pharmaceutical scientist, researcher, and former vice-chancellor of the University of Abuja. Renowned for his pioneering work in pharmaceutical sciences, including the innovative use of snail mucin in wound healing, he has become a beacon of excellence in Nigeria’s academic landscape and beyond. In this exclusive interview with Ola Aboderin, the award-winning scientist shares the highlights of his remarkable career, his tenure as vice-chancellor, and his unwavering commitment to advancing pharmaceutical education and research in Nigeria. Excerpts:

Kindly tell us about your background and academic journey.

I was born on 19 April 1963. I attended St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Primary School, Benue State, from 1969 to 1975. Following this, I gained admission to Federal Government College, Jos, in 1976. I completed secondary school in 1981 and gained admission to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, the same year.

I graduated from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1986. After graduation, I worked as a hospital pharmacist from 1986 to 1990, including my internship and National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) programme. In 1990, I joined the University of Nigeria’s service and rose to the rank of professor in 1998. I teach and research various aspects of pharmaceutical education, particularly in raw materials utilisation and sustainability, as well as health sector reforms and public health.

Eight of my postgraduate students are currently professors of Pharmacy in various universities, and one of them has just completed a tenure as vice-chancellor at Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State.

What motivated you to study Pharmacy?

As a young student, I had friends who were keen on studying Medicine. However, I was more interested in studying economics. My primary concern was the financial aspect of education, and I sought a course that would conclude in a few years, which economics offered. Eventually, I decided to study pharmacy, believing it would allow me to advance quickly in the field. Fortunately, I received a Federal Merit Award and was granted a scholarship from my second year onward.

Growing up in a village, I was very playful and observed how certain plants and roots could be used as medicine. My mother often sent me to the forest to dig up roots of Alchormenea deformis, which she would boil to treat my younger siblings who had malaria and other ailments. These early experiences inspired me to pursue a career in pharmacy, reinforcing the idea that childhood experiences can shape one’s future.

Tell us about your career path since graduating from pharmacy school to date.

My career path has been quite interesting. After graduating, I attended interviews at two places and was offered positions at both, but the first offer, from my state of Benue, came through first. I had told my undergraduate project supervisor, an Indian, that I wanted to return to academia. I had done a review on the use of genetic engineering, which sparked my interest in research. My work included issues about lymphocyte hybridoma. When the interview results came out in my state, I started my internship at the General Hospital Makurdi. Later, when the results from my university in Nsukka were released, I resigned and returned there.

The Faculty of Pharmacy had just started taking people for internships, which allowed interns to stay at the faculty for some time and attend practical sessions with students before gaining experience at the University Medical Centre. During this period, I bought postgraduate forms and was admitted. I chose the Indian supervisor and began my master’s degree work on taste-masking chloroquine through microencapsulation. I spent almost all my time in the laboratory, and by the time I finished my internship, I had completed my practical work. However, I was not allowed to graduate because I had not completed my National Youth Service. So, I left for my Youth Service programme in Kwara State in 1987/1988.

When I finished, I returned to my state as a hospital pharmacist. Benue is adjacent to Enugu State, so I took permission one day and went to Nsukka. I was informed that my supervisor had left, but my head of department said he would read my work. I had to wait since a master’s degree on a part-time basis was 18 months. I didn’t do any coursework because, in that era, if you graduated with a first-class or second-class upper, you could be exempted from coursework if you wished. By July 1989, I defended my master’s degree. By September 1989, I resigned from the Health Management Board of Benue State and went to the University of Jos in Plateau State.

The university appointed me as an assistant lecturer, but I was unhappy with that position and argued that I should be placed as a lecturer II. They refused, so I resigned after teaching there for just five months and returned to my alma mater, Nsukka. I had gone to Jos earlier because I did my secondary education at the Federal Government College, Jos, so it was painful for me to leave. At Nsukka, I quickly settled into academia.

One man approached me and asked if I could work locum in his shop. Another pharmacist had registered but was not actually working there, so I agreed to fill the gap. At the time, my salary was only about 714 Naira, and the man was willing to pay me 500 Naira. During this period (1991), the Federal Ministry of Health had just promulgated a decree on the Essential Drugs List (1989). Under that decree, fixed-ratio combination drugs were discouraged except where a drug would lose its activity, such as with some antimicrobials and antimalarials. Pain relievers, like Panadol, were banned from containing aspirin, paracetamol, and caffeine. However, Panadol was still marketed as containing only paracetamol. I decided to document the number of people requesting generic and branded products and wrote an article which I sent to The Lancet. The Lancet asked me to reduce it to 1,000 words and one table, which I reluctantly did.

After about three years (two years and eight months), I applied for promotion to lecturer I. The professor in charge of promotions in the faculty called me and said that publishing in The Lancet was a significant achievement, so he would recommend me for senior lecturer. That was how I became a senior lecturer in less than three years, promoted ahead of my seniors.

After another three years, I applied for the position of professor with 41 research papers. I was denied because the university was in turmoil at the time. The internal reviewer had given me 53 out of 65 points, not knowing the rules. I only needed 50 points. The authorities stated that any publication outside the United Kingdom and the United States would not be accepted. As a result, my score was reduced to 36.5, which meant I didn’t get the promotion. Some of our lecturers left the university because the disputes were intense. I had to apply again in 1998 with 61 papers. This time, I scored 50, not the 53 I had achieved with 41 papers. Fortunately, despite all the delays, I was promoted with that submission.

In 1999, I went for an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship at the University of Dusseldorf (Heinrich Heine University) in Germany. In 2002, I went to Kyoto Pharmaceutical University in Japan as a Matsumae Fellow. In 2006, I was a Royal Society Fellow at the University of Manchester, but this was interrupted after I won a Nigerian fellowship, which I had applied for before leaving the country. This was still part of the research I went to do in Germany. Unfortunately, I could not return as I was called to coordinate a World Bank-assisted project at the Federal Ministry of Education in Abuja. After coordinating the World Bank-assisted project, I became vice-chancellor at the University of Abuja, Nigeria.

You became a professor at the unprecedented age of 35. How did this happen?

As I mentioned earlier, if not for the conflicts that arose at the University during my early academic years, I might have become a professor even sooner. Part of the story has already been told. During that time, promotions typically occurred every three years at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Another factor that contributed to my early promotion was that I was a very curious village boy who turned the objects I played with into research materials.

While conducting my research, I consistently submitted my work for publication. When I was advised to begin my PhD, I had to find materials for my research. I quickly thought of an African latex from a plant called Landolphia dulcis. As a child, I would add lime juice to it, making it very sticky. I used this sticky substance, smeared on a broomstick, to catch birds by attracting termites. When birds came to pick the termites, they would get stuck to the latex.

I later read in the literature that such latexes could be converted into pseudolatex, becoming creamy or milky when mixed with benzene or dioxane. I began experimenting with that, and at each stage, I submitted my work for publication to guide my next steps. The feedback from reviewers helped me strengthen my research and produce more publications.

After a year, my supervisor suggested that I change my research focus, as using a new rubbery material for a PhD could be challenging, particularly when it came to determining the molecular weight. I quickly returned home and looked for another gummy material. Our mothers used a substance from an African plant called Prosopis africana. The seeds of this plant are boiled, and the seed coat, which consists of a tegmen and a hard outer layer, is removed. I collected the tegmen, mashed it, and soaked it for 24 hours. After dissolving it in water and precipitating it with alcohol, I could easily determine its molecular weight.

Initially, I intended to prepare a bacteriological medium similar to agar, but I realised that would take too long. Instead, I decided to use this mucilaginous material for various pharmaceutical formulations. As I applied it in different formulations, from suspensions to disintegrants, I continued to submit each paper to journals outside Nigeria.

By the time each promotion period came around, I had more than enough publications. Thus, becoming a professor at the age of 35 was not particularly difficult or a big deal for me.

Could you share other significant highlights of your career with us?

In 2007, I was appointed the National Coordinator of Science and Technology Education Post Basic (STEP-B), a project aimed at improving the post-basic and higher education system in Nigeria through the World Bank IDA system. Under this project, eleven Centres of Excellence emerged, each addressing various national needs.

As previously mentioned, I have gained both local and international experience in the pharmaceutical field, particularly in education and research. I have had the opportunity to visit overseas laboratories three times: as an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in Germany (1999–2000), a Matsumae Fellow in Japan (2002), and a Royal Society Fellow in Manchester, United Kingdom (2006). In terms of international grants, I have secured research funding from the Royal Society of Chemistry of Great Britain (2002); the Third World Academy of Sciences, Italy (2004); and the International Foundation for Science, Sweden (2004). Locally, I have been awarded grants from the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development (NIPRD), Abuja, and the Wellcome Nigeria Trust, Lagos.

I have also received training at the World Bank Institute in Washington, USA; the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Boston, USA; and the Hebrew University in Israel on Innovations in Higher Education. Additionally, I have undergone training at the Galilee Management Institute in Israel, the Third World Academy of Sciences (now The World Academy of Sciences) in Trieste, Italy, on Bioinformatics and Drug Development, and on Entrepreneurship at the E4Impact Foundation at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, Italy, as well as at the University of the West of Scotland in Britain.

I am a Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Science (FAS), the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria (FPSN), and the Science Association of Nigeria (FSAN). I am also an Honorary Fellow of the Science Teachers’ Association of Nigeria (FSTAN) and the Entomological Society of Nigeria (FESN). Additionally, I am a Member of the Institute of Public Analysts of Nigeria (MIPAN), a Fellow of the African Scientific Institute (FASI), the Chartered Institute of Leadership and Governance (FCILG, USA), the Institute of Oil and Gas Research (FIOGR), and the International Society of Comparative Education, Science and Technology (FISCEST). I am also the founding President of the Nanomedicine Society of Nigeria. I served as the Vice Chancellor of the University of Abuja, Nigeria, from June 2014 to June 2019.

I was awarded Fellowship of the Nigerian Academy of Pharmacy and Fellowship of the Institute of Public Analysts of Nigeria but did not attend the investiture ceremonies.

In 2006, you won the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Science with your work on “Wound Healing Devices (Formulations) Containing Snail Mucins.” Can you tell us more about the work? What did this award mean to you?

In 1999-2000, I was an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in Germany. During the onset of spring in April, while heading to the computer laboratory, I was surprised to see numerous slugs on the ground. At that time, I was focused on molecular modelling work, using computer algorithms for my postdoctoral fellowship. The sight of slugs in such a cold environment was astonishing to me. How could these shell-less creatures survive in such harsh conditions? While snails might have managed with their shells, slugs seemed miraculous in the temperate climate of Germany.

When I returned to Nigeria, I searched for slugs but couldn’t find any, so I decided to study snails instead. Both snails and slugs are mollusks belonging to the Gastropoda family. The results of my research on snails were fascinating. Beyond their wound-healing properties, snail mucins possess antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral characteristics. They also exhibit promising drug delivery properties. My current focus has shifted to slug mucin, as slugs were the organisms I initially intended to study. It’s also important to note that data from snails and slugs can inform environmental policies. In the past, when snails were abundant, other organisms like mushrooms thrived in the forests. However, with the decline of snails due to bush burning and deforestation, mushrooms have also disappeared. These mushrooms were once a key culinary resource for villagers.

Winning the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Science was a significant milestone for me. It was this award that led to my invitation to coordinate a World Bank-assisted project. Beyond the monetary value, the award opened doors for me, exposing me to places and people I never would have encountered otherwise. I am deeply grateful to God for this achievement.

What other major awards and recognitions have you received since the beginning of your career, and which would you consider most fulfilling so far?

In addition to winning the Nigerian Prize for Science (2006), I was honoured with the May & Baker Prize for Excellence in the Practice of Pharmacy (2009). In 2019, I received The World Academy of Science Prize for Development of Materials for Use in Science and Technology. During my secondary school years, I won the Federal Merit Award (scholarship) for being one of the top three students in my class. Later, at university, I was again awarded the Federal Merit Award (scholarship) as one of the top 20 first-year students at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.