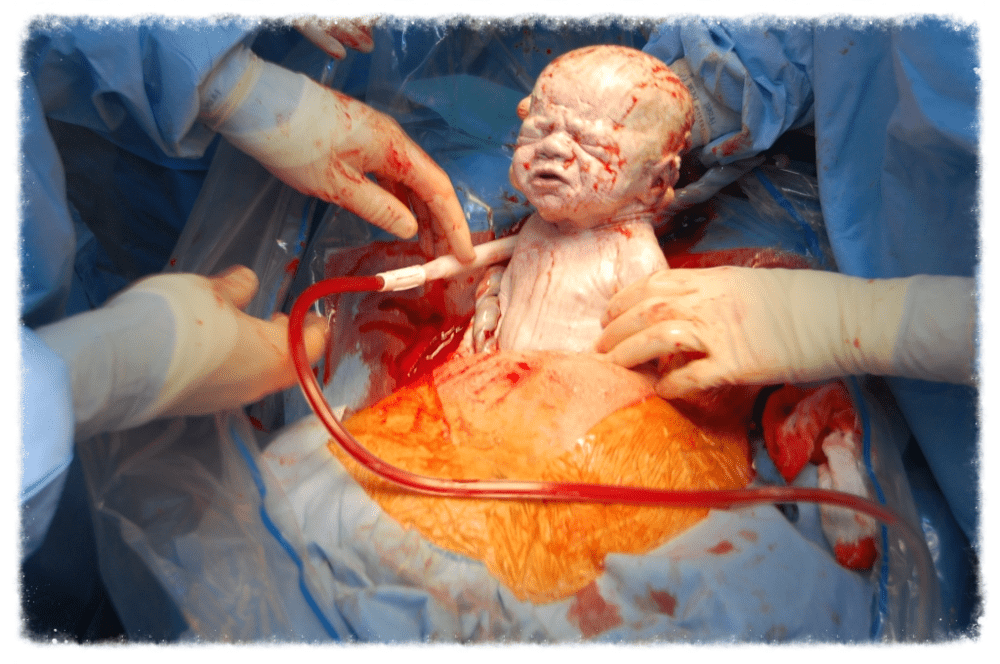

A new study conducted by researchers from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden has revealed that infants born by caesarean section initially have less diverse gut bacteria than those delivered through vagina, but they catch up within a few years.

They also found that it takes a long time for these bacteria colonies—known as the gut microbiome—to mature.

Fredrik Backhed, a professor of molecular medicine from the university said their findings show that the gut microbiota is a dynamic organ, and future studies will have to show whether the early differences can affect the cesarean children later in life.

For the study, his team took fecal samples from 471 newborns, and again when they were 4 months, 12 months, 3 years and 5 years old. The samples were analysed for gut bacteria.

It was already known that at birth, an infant's intestine has already been colonised by bacteria and other microorganisms, and that the diversity of those species increases in the first few years of life.

This study provides more detailed information about development of the gut microbiome. The study found out that even at 5 years of age, it's incomplete.

How long it takes for the gut microbiome to mature differs from child to child, and this study found that babies delivered by C-section initially had less diverse gut bacteria than infants delivered through the vagina.

But by the time they reached 3 to 5 years of age, the diversity of gut bacteria was similar in both groups, according to findings published online March 31 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

“It's striking that even at the age of 5 years, several of the bacteria that are important components of the intestinal microbiota in adults are missing in the children,” Bäckhed said in a university news release.

That shows that the intestine is a complex and dynamic environment where bacteria create conditions for colonization by one another, he added.

“By investigating and understanding how the intestinal microbiota develops in healthy children, we may get a reference point to explore if the microbiota may contribute to disease in future studies,” Bäckhed said.