Researchers now view glaucoma as a disease of the brain — a neurodegenerative disease — rather than simply an eye disease. Recent research has shown that the complex connection between the eye and the brain is an important key to the disease.

Glaucoma shares a number of features with degenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Lou Gehrig’s disease. In all of these diseases, age and family history are significant risk factors, and specific areas of the brain are damaged over time. In glaucoma, the only difference is that the “specific area of the brain” affected is the eye and optic nerve!

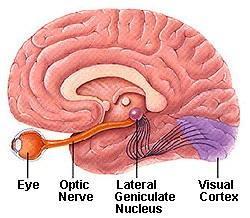

Indeed the eye’s retina and optic nerve are a part of the brain: during early development, a small part of the brain pouches out and becomes the retina and optic nerve. Inside the eye, a group of neurons called retinal ganglion cells collect all of the visual information and pass it down their extensions, called axons, through the optic nerve and back to the rest of the brain. The ganglion cell, which collects all the vision information from the other retinal cells, is the one type of cell that is initially damaged by glaucoma.

The optic nerve continues to be a major focus for researching the underlying causes of glaucoma. Whether due to mechanical trauma, decreased blood flow, or other causes, optic nerve axon injury causes changes in retinal ganglion cells, eventually causing cell death. Researchers have observed that specific areas of injured optic nerve axons and retinal ganglion cell loss match the peripheral vision damage from glaucoma.

Because the retinal ganglion cell axon stretches from the retina through the optic nerve to the brain, its surrounding cells also become damaged by glaucoma. Within the retina, other cells, such as amacrine cells, degenerate and rewire their connections after retinal ganglion cells are lost.

There are also changes in the brain within the lateral geniculate nucleus (the main brain target of optic nerve axons), and even the visual cortex, which is the part of the brain that helps us interpret visual information.

Thus, in addition to treatments directed at lowering eye pressure, still the mainstay of glaucoma therapy, there may be opportunities to develop treatments directed at the retina and the brain. Some promising treatments that promote nerve health, called neurotrophic factors, could help at multiple places in the visual pathway.

For example, neurotrophic factors such as ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) may keep retinal ganglion cells from dying, a process called neuroprotection; they may increase axon regrowth down the optic nerve, called regeneration; and they may improve the support between the dying retinal ganglion cells and their surrounding cells in the retina and brain, called neuroenhancement.

The understanding that one key to glaucoma is in the connections within the retina and to the brain has led to exciting advances in research that may well lead to new potential treatments.

Article by Jeffrey L. Goldberg, MD, PhD, Professor and Chair of Ophthalmology at the Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University School of Medicone.

Source: www.glaucoma.org