Until recent times, overcoming the malaria burden had been a tall order for many countries across the world. Within the past decade however four of such countries have been certified by the WHO Director-General as having eliminated malaria. These include the United Arab Emirates (2007), Morocco (2010), Turkmenistan (2010), and Armenia (2011). In 2014, 16 countries reported zero cases of malaria within their borders. Another 17 countries reported fewer than 1000 cases of malaria.

Unfortunately, a major part of Sub-Saharan Africa still carries a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden. In 2015, the region was home to 88 per cent of malaria cases and 90 per cent of malaria deaths.

It is in view of this that the World Malaria Day 2016 is themed: “End Malaria For Good”, canvassing concerted efforts to build on the success achieved under the Millennium Development Goals to be transformed to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female mosquitoes called Anopheles mosquitoes. There are five parasite species that cause malaria in humans, and two of these – P. falciparum and P. vivax – pose the greatest threat.

‘ P. falciparum is the most prevalent malaria parasite on the African continent. It is responsible for most malaria-related deaths globally. P. vivax has a wider distribution than P. falciparum, and predominates in many countries outside of Africa.

Malaria statistics

About 3.2 billion people – almost half of the world’s population – are at risk of malaria. Young children, pregnant women and non-immune travellers from malaria-free areas are particularly vulnerable to the disease when they become infected. Malaria is preventable and curable, and increased efforts are dramatically reducing the malaria burden in many places.

Between 2000 and 2015, malaria incidence among populations at risk (the rate of new cases) fell by 37 per cent globally. In that same period, malaria death rates among populations at risk fell by 60 per cent globally among all age groups, and by 65 per cent among children under five.

Causes of malaria

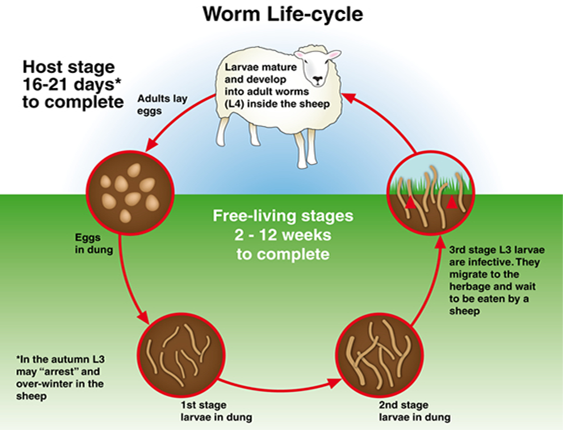

When an infected mosquito bites a human host, the parasite enters the bloodstream and lays dormant within the liver. For the next five to 16 days, the host will show no symptoms but the malaria parasite will begin multiplying asexually. The new malaria parasites are then released back into the bloodstream where they infect red blood cells and again begin to multiply. Some malaria parasites, however, remain in the liver and are not released until later, resulting in recurrence.

An unaffected mosquito becomes infected once it feeds on an infected individual, thus beginning the cycle again.

Symptoms of malaria

Malaria symptoms can be classified in two categories: uncomplicated and severe malaria. Uncomplicated malaria is diagnosed when symptoms are present, but there are no clinical or laboratory signs to indicate a severe infection or the dysfunction of vital organs. Individuals suffering from this form can eventually develop severe malaria if the disease is left untreated, or if they have poor or no immunity to the disease.

Symptoms of uncomplicated malaria typically last six to ten hours and occur in cycles that occur every second day, although some strains of the parasite can cause a longer cycle or mixed symptoms. Symptoms are often flu-like and may be undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in areas where malaria is less common. In areas where malaria is common, many patients recognize the symptoms as malaria and treat themselves without proper medical care.

Uncomplicated malaria typically has the following progression of symptoms through cold, hot and sweating stages:

- Sensation of cold, shivering

- Fever, headaches, and vomiting (seizures sometimes occur in young children)

- Sweats, followed by a return to normal temperature, with tiredness.

Severe malaria is defined by clinical or laboratory evidence of vital organ dysfunction. This form has the capacity to be fatal if left untreated. As a general overview, symptoms of severe malaria include:

- Fever and chills

- Impaired consciousness

- Prostration (adopting a prone or prayer position)

- Multiple convulsions

- Deep breathing and respiratory distress

- Abnormal bleeding and signs of anaemia

- Clinical jaundice and evidence of vital organ dysfunction.

Who is at risk?

Most malaria cases and deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa. However, Asia, Latin America, and, to a lesser extent, the Middle East, are also at risk. In 2015, 97 countries and territories had on-going malaria transmission.

Some population groups are at considerably higher risk of contracting malaria, and developing severe disease, than others. These include infants, children under five years of age, pregnant women and patients with HIV/AIDS, as well as non-immune migrants, mobile populations and travellers. National malaria control programmes need to take special measures to protect these population groups from malaria infection, taking into consideration their specific circumstances.

Malaria in Nigeria

Experts in the health sector have identified Nigerians’ reluctant attitude towards science-proven interventions as a bane to the fight against malaria in the country. They, therefore, reiterate that sleeping on treated insecticide nets every night is key to achieving a malaria-free nation.

The National Coordinator, National Malaria Elimination Programme, Dr Nnenna Ezeigwe, recently lamented the negative attitude of most Nigerians towards the initiative, by being reluctant in adopting the strategies and intervention, which according to her, has greatly hampered the progress in malaria control.

She said, “low uptake of interventions is one of the problems militating fast progress in the fight against malaria/”

Ezeigwe also called on Nigerians to embark on environmental management, saying “Individuals should keep their environment clean and clear all bodies of water in the general environment. They should observe general hygiene and always sleep under the net every night.”

On his part, the Country Director of Malaria Consortium, Dr Kolawole Maxwell, disclosed that the UK government through the Department for International Development (DFID) has invested over 89 million pounds to support the malaria programme in eight years (2008-2016), in Nigeria.

According to him, the essence was to reach the general population, especially, the poorest and most vulnerable with evidence based interventions that would help control the disease and reduce the malaria burden.

Transmission of malaria

In most cases, malaria is transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes. There are more than 400 different species of Anopheles mosquito; around 30 are malaria vectors of major importance. All of the important vector species bite between dusk and dawn. The intensity of transmission depends on factors related to the parasite, the vector, the human host, and the environment.

Anopheles mosquitoes lay their eggs in water, which hatch into larvae, eventually emerging as adult mosquitoes. The female mosquitoes seek a blood meal to nurture their eggs. Each species of Anopheles mosquito has its own preferred aquatic habitat; for example, some prefer small, shallow collections of fresh water, such as puddles and hoof prints, which are abundant during the rainy season in tropical countries.

Transmission is more intense in places where the mosquito lifespan is longer (so that the parasite has time to complete its development inside the mosquito) and where it prefers to bite humans rather than other animals. The long lifespan and strong human-biting habit of the African vector species is the main reason why nearly 90 per cent of the world’s malaria cases are in Africa.

Transmission also depends on climatic conditions that may affect the number and survival of mosquitoes, such as rainfall patterns, temperature and humidity. In many places, transmission is seasonal, with the peak during and just after the rainy season. Malaria epidemics can occur when climate and other conditions suddenly favour transmission in areas where people have little or no immunity to malaria. They can also occur when people with low immunity move into areas with intense malaria transmission, for instance to find work, or as refugees.

Human immunity is another important factor, especially among adults in areas of moderate or intense transmission conditions. Partial immunity is developed over years of exposure, and while it never provides complete protection, it does reduce the risk that malaria infection will cause severe disease. For this reason, most malaria deaths in Africa occur in young children, whereas in areas with less transmission and low immunity, all age groups are at risk.

Malaria and pregnancy

Malaria is a serious illness, particularly for pregnant women. It can result in severe illness or death, and affects both the mother and unborn baby.

Your GP will advise you which, if any, anti-malaria medication to take. Remember to take it regularly and exactly as prescribed.

You can take some anti-malaria medicines safely during pregnancy, but should avoid others. For example:

- Chloroquine and proguanil (usually combined) can be used in pregnancy, but may not offer enough protection against malaria in many regions, including Africa; you will also need to take a 5mg supplement of folic acid if you’re taking proguanil (if you’re in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, remember to continue with your usual 400 microgram folic acid supplement after you stop taking the proguanil – while you’re taking the 5mg supplement, you don’t need to take the 400 micrograms as well)

- mefloquine should not be taken during your first trimester (the first 12 weeks of pregnancy)

- doxycycline should not be taken at all during pregnancy

- atovaquone/proguanil should not be taken at all during pregnancy as there is a lack of evidence that it is safe to use in pregnancy

Taking the steps below will help you to avoid mosquito bites:

- Use a mosquito repellent on your skin – choose one specifically recommended for use in pregnancy and apply it often, following the manufacturer’s instructions

- Cover your arms and legs by wearing long-sleeved tops and long trousers after sunset

- Use a spray or coil in your room to kill any mosquitoes before you go to bed

- Sleep in a properly screened, air-conditioned room or under a mosquito net that’s been treated with insecticide – make sure the net is not broken

- Ideally, pregnant women should remain indoors between dusk and dawn

Prevention of malaria

Vector control is the main way to prevent and reduce malaria transmission. If coverage of vector control interventions within a specific area is high enough, then a measure of protection will be conferred across the community.

WHO recommends protection for all people at risk of malaria with effective malaria vector control. Two forms of vector control – insecticide-treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying – are effective in a wide range of circumstances.

Insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs)

Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) are the preferred form of ITNs for public health programmes. In most settings, WHO recommends LLIN coverage for all people at risk of malaria. The most cost-effective way to achieve this is by providing LLINs free of charge, to ensure equal access for all. In parallel, effective behaviour change communication strategies are required to ensure that all people at risk of malaria sleep under a LLIN every night, and that the net is properly maintained.

Indoor spraying with residual insecticides

Indoor residual spraying (IRS) with insecticides is a powerful way to rapidly reduce malaria transmission. Its full potential is realized when at least 80 per cent of houses in targeted areas are sprayed. Indoor spraying is effective for three to six months, depending on the insecticide formulation used and the type of surface on which it is sprayed. In some settings, multiple spray rounds are needed to protect the population for the entire malaria season.

Antimalarial medicines can also be used to prevent malaria. For travellers, malaria can be prevented through chemoprophylaxis, which suppresses the blood stage of malaria infections, thereby preventing malaria disease.

For pregnant women living in moderate-to-high transmission areas, WHO recommends intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, at each scheduled antenatal visit after the first trimester. Similarly, for infants living in high-transmission areas of Africa, three doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine are recommended, delivered alongside routine vaccinations.

In 2012, WHO recommended Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention as an additional malaria prevention strategy for areas of the Sahel sub-Region of Africa. The strategy involves the administration of monthly courses of amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine to all children under five years of age during the high transmission season.

Insecticide resistance

Much of the success in controlling malaria is due to vector control. Vector control is highly dependent on the use of pyrethroids, which are the only class of insecticides currently recommended for ITNs or LLINs.

In recent years, mosquito resistance to pyrethroids has emerged in many countries. In some areas, resistance to all 4 classes of insecticides used for public health has been detected. Fortunately, this resistance has only rarely been associated with decreased efficacy of LLINs, which continue to provide a substantial level of protection in most settings. Rotational use of different classes of insecticides for IRS is recommended as one approach to manage insecticide resistance.

However, malaria-endemic areas of sub-Saharan Africa and India are causing significant concern due to high levels of malaria transmission and widespread reports of insecticide resistance. The use of two different insecticides in a mosquito net offers an opportunity to mitigate the risk of the development and spread of insecticide resistance; developing these new nets is a priority. Several promising products for both IRS and nets are in the pipeline.

Detection of insecticide resistance should be an essential component of all national malaria control efforts to ensure that the most effective vector control methods are being used. The choice of insecticide for IRS should always be informed by recent, local data on the susceptibility of target vectors.

To ensure a timely and coordinated global response to the threat of insecticide resistance, WHO worked with a wide range of stakeholders to develop the Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management in Malaria Vectors (GPIRM), which was released in May 2012.

Diagnosis and treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment of malaria reduces disease and prevents deaths. It also contributes to reducing malaria transmission. The best available treatment, particularly for P. falciparum malaria, is artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT).

WHO recommends that all cases of suspected malaria be confirmed using parasite-based diagnostic testing (either microscopy or rapid diagnostic test) before administering treatment. Results of parasitological confirmation can be available in 30 minutes or less. Treatment, solely on the basis of symptoms should only be considered when a parasitological diagnosis is not possible. More detailed recommendations are available in the “WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, third edition”, published in April 2015.

Antimalarial drug resistance

Resistance to antimalarial medicines is a recurring problem. Resistance of P. falciparum to previous generations of medicines, such as chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), became widespread in the 1970s and 1980s, undermining malaria control efforts and reversing gains in child survival.

WHO recommends the routine monitoring of antimalarial drug resistance, and supports countries to strengthen their efforts in this important area of work.

An ACT contains both the drug artemisinin and a partner drug. In recent years, parasite resistance to artemisinins has been detected in five countries of the Greater Mekong subregion: Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. Studies have confirmed that artemisinin resistance has emerged independently in many areas of this sub-region.

There are concerns that P. falciparum malaria in Cambodia and Thailand is becoming increasingly difficult to treat, and that multi-drug resistance could spread to other regions with dire public health consequences. Consequently, WHO’s Malaria Policy Advisory Committee in September 2014 recommended adopting the goal of eliminating P. falciparum malaria in this sub-region by 2030. WHO launched the Strategy for Malaria Elimination in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (2015–2030) at the World Health Assembly in May 2015, which was endorsed by all the countries in the sub-region.

Surveillance

Surveillance entails tracking of the disease and programmatic responses, and taking action based on the data received. Currently, many countries with a high burden of malaria have weak surveillance systems and are not in a position to assess disease distribution and trends, making it difficult to optimize responses and respond to outbreaks.

Effective surveillance is required at all points on the path to malaria elimination. Strong malaria surveillance enables programmes to optimise their operations, by empowering programmes to:

- advocate for investment from domestic and international sources, commensurate with the malaria disease burden in a country or subnational area;

- allocate resources to populations most in need and to interventions that are most effective, in order to achieve the greatest possible public health impact;

- assess regularly whether plans are progressing as expected or whether adjustments in the scale or combination of interventions are required;

- account for the impact of funding received and enable the public, their elected representatives and donors to determine if they are obtaining value for money; and

- evaluate whether programme objectives have been met and learn what works so that more efficient and effective programmes can be designed.

Stronger malaria surveillance systems are urgently needed to enable a timely and effective malaria response in endemic regions, to prevent outbreaks and resurgences, to track progress, and to hold governments and the global malaria community accountable.

Elimination

Malaria elimination is defined as interrupting local mosquito-borne malaria transmission in a defined geographical area, typically countries; i.e. zero incidence of locally contracted cases. Malaria eradication is defined as the permanent reduction to zero of the worldwide incidence of malaria infection caused by a specific agent; i.e. applies to a particular malaria parasite species.

According to the latest estimates from WHO, more than half (57) of the 106 countries with malaria in 2000 had achieved reductions in new malaria cases of at least 75 per cent by 2015, in line with targets set by the World Health Assembly. An additional 18 countries reduced their malaria cases by 50-75 per cent.

Large-scale use of WHO-recommended strategies, currently available tools, strong national commitments, and coordinated efforts with partners, will enable more countries – particularly those where malaria transmission is low and unstable – to reduce their disease burden and progress towards elimination.

Vaccines against malaria

There are currently no licensed vaccines against malaria or any other human parasite. One research vaccine against P. falciparum, known as RTS, S/AS01, is most advanced. This vaccine has been evaluated in a large clinical trial in seven countries in Africa and received a positive opinion by the European Medicines Agency in July 2015.

In October 2015, two WHO advisory groups recommended pilot implementations of RTS,S in a limited number of African countries. These pilot projects could pave the way for wider deployment of the vaccine in three to five years, if safety and effectiveness are considered acceptable.

The WHO Global Malaria Programme (GMP) coordinates WHO’s global efforts to control and eliminate malaria by:

- setting, communicating and promoting the adoption of evidence-based norms, standards, policies, technical strategies, and guidelines;

- keeping independent score of global progress;

- developing approaches for capacity building, systems strengthening, and surveillance; and

- identifying threats to malaria control and elimination as well as new areas for action.

GMP is supported and advised by the Malaria Policy Advisory Committee (MPAC), a group of 15 global malaria experts appointed following an open nomination process. The MPAC, which meets twice yearly, provides independent advice to WHO to develop policy recommendations for the control and elimination of malaria. The mandate of MPAC is to provide strategic advice and technical input, and extends to all aspects of malaria control and elimination, as part of a transparent, responsive and credible policy setting process.

Report compiled by Temitope Obayendo with resources from The World Health Organisation and the Leadership newspaper.