I was drawn to the subject of the New Drug Distribution Guidelines again by my amiable friend and erudite scholar, Professor Chinedum Babalola. I have spent four years (2013 – 2016), as the Chairman of the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria’s National Drug Distribution Committee, working on the guidelines and I had cause to travel round the country to preach the message of a sanitised drug distribution system and the need for pharmacists to rise to the occasion and seize the moment for a professional rebirth.

I was drawn to the subject of the New Drug Distribution Guidelines again by my amiable friend and erudite scholar, Professor Chinedum Babalola. I have spent four years (2013 – 2016), as the Chairman of the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria’s National Drug Distribution Committee, working on the guidelines and I had cause to travel round the country to preach the message of a sanitised drug distribution system and the need for pharmacists to rise to the occasion and seize the moment for a professional rebirth.

I thought I needed a break to reflect more on what we had done and listen to other views on the subject, but the brilliant professor would not let me be as she insisted on my being a guest speaker on “National Drug Distribution Guidelines and its Benefits” at the International Conference on “Improving Access to Quality Medicines through appropriate Legislations and Policies” organised by the Centre for Drug Discovery, Development & Production, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ibadan. This article is based on my address at the well-attended conference on Tuesday, 29 August 2017.

Nature of medicines

Medicines are made (and are meant) to do good and the Scripture recognises this fact when it states: “A merry heart doeth good like medicine” (Proverbs 22:17). Therefore, it is not a surprise that people seek to use drug for the promotion of healthy living and as a remedy when they are in health distress. However, in our environment, we have had so many instances where medicines no longer do good. In many of these cases, the conditions of the patients got worse and some even led to death.

Cases in which medicines ‘no longer do good’ occur particularly when: they are not available at the point of need; they are available but not at the right time and quantity; they are available as adulterated or outright fake; they are available and can be accessed in or at wrong places; or when they are available in the wrong hands and not handled by the experts.

According to William Osler, a Canadian physician and one of the four founding professors of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, “The desire to take medicine is perhaps the greatest feature which distinguishes man from animals.” In other words, the use of medicines is a veritable evidence of the wisdom of man.

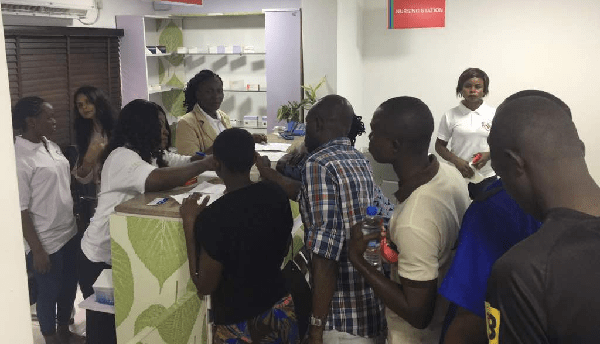

It is such a wonder, therefore, that we have not been able to handle medicines properly in this part of the world. Drugs are industrially manufactured and require distribution to reach the final consumer, the patient. Distribution of drugs requires efficient supply chain systems and appropriate regulation to ensure that the medicines that reach the consumer are in their intended qualitative state, supported with the required infrastructure to ensure rational use.

We have made some progress in drug production (despite the yawning gaps) but we have not done much in entrenching a distribution system that ensures that the medicines that get to the end users (i.e. the final consumers) are effective, qualitative, safe and affordable. This is the challenge before all of us as professionals, policy formulators and other stakeholders. It was in an attempt to face this challenge squarely that the federal government released the New Drug Distribution Guidelines (NDDG) in 2012.

Basis of NDDG

There are different drug distribution models used worldwide to achieve the lofty objective of uniform access to quality medicines by those who need them. The model in Figure 1 below is used mostly in developed countries. Most of the consumers of health products receive their medicines through physician’s offices, pharmacies and dispensaries and there is a cohesive drug distribution and effective regulatory framework to assure the quality of the final product that reaches consumers.

In developing countries like Nigeria, the drug distribution infrastructure is fragmented and inefficient, resulting in a preponderance of fake, adulterated and substandard products infiltrating the market because of the activities of unscrupulous elements. The network is inept and complex, and due to technical inefficiencies, regulation is made ineffective. This leads to the flow of fake, adulterated and substandard products to the final consumer.

The NDDG, aimed at establishing a well-ordered drug distribution system in Nigeria, is the result of the cumulative efforts of stakeholders in the health sector from 2009 to 2012. The objectives outlined are very clear and altruistic: reduction in the levels of adulterated and fake drugs in the market; elimination of the dominance of unregulated drug markets in major cities of the country; breaking of the stranglehold of the informal sector on drugs distribution; facilitation of the oversight role of relevant federal government of Nigeria agencies; and ensuring that all drugs in the national drug distribution system are safe, efficacious, effective, affordable, and of good quality.

The NDDG framework, as depicted in figure 3 below, was initially composed of Mega Drug Distribution Centers (MDDCs), States Drug Distribution Centers (SDDCs), wholesalers and retail outlets, in a hierarchical order to be operated by the private and public sectors. Regulatory agencies were recognised within the framework, including the Pharmacist Council of Nigeria (PCN) and the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC).

Figure 3: NDDG approved channels

The guidelines also make provision for the set-up, organisation and administration of each level in the distribution chain. The administrative guidelines are more explicit at the State Drug Distribution Centre level because of the government’s involvement and the need to accommodate public governance process.

The original framework as described above was criticised by some stakeholders, particularly the manufacturing group. They felt that their interest was not accommodated well enough and they called for amendment. In response to the criticisms, the concept of Coordinated Wholesale Centres was added to pander to entrenched interests and drive acceptability by every stakeholder as shown in Figure 4 below:

The NDDG allowed for drug entry into the distribution cycle through the importers and manufacturers, who must have been registered by the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria (PCN).

Barriers to implementation

While we are usually very good at formulating policies, we remain consistently poor at implementation. The national ‘shelves’ are full of well-crafted policy documents that are gathering dusts and begging for implementation. A typical example is the ‘National Drug Policy, 2005’ which prescribed that a certain percentage of drug purchases by government agencies should be reserved for local manufacturers. Till date, the policy is not better than the paper with which it was printed. This is a national malaise that requires urgent attention from all and sundry.

Unfortunately, this malaise has also affected the implementation of the NDDG and the effective date of the implementation has been shifted three times already. The rhetoric is the same at each postponement announcement and the excuses can be extrapolated to the next one. Now, we are told that January 2019 is the new implementation date and your guess is as good as mine if this date will be sacrosanct.

The implementation challenges can be attributed to many factors, including lack of knowledge. People have not taken time to study the guidelines deeply to understand and appreciate its provisions. This lack of knowledge gave room to fears and therefore, opposition.

There is also lack of programme or project ownership. At the beginning, the ownership of the implementation was not clear and this made the NDDG an orphan. For seamless or effective execution, we need to have a clear ownership, with the passion to get things done. It was this passion that drove our activities in the ‘National Drug Distribution Committee’ and which gave birth to Ultra Logistics Company Limited.

Selfish interest is another factor because, as with most things in this clime, those who are benefiting from the current situation will do everything possible to prevent a change. There is lack of vision; we are too fixated on today’s affairs that we fail to see the benefits that our current action can bring in the near and far future.

Again, lack of affirmative action on the part of the government which needs to be firm in taking some actions, even if it is not so popular or its immediate benefits cannot be seen now. After all, it is stated that ‘you cannot eat omelette without breaking an egg’. We should always beware of ‘analysis that breeds paralysis’.

Progress path

There is a need to stop the cycle of ‘we are not ready yet’, as unending analysis will paralyse the system. We should be ready to take ‘baby steps’ that will lead us to the destination.

We took several baby steps during the committee work. We got pharmacists to be aware of the guidelines and we set up a ‘special purpose vehicle’ to demonstrate the possibilities. In February 2015, we opened the first account for the company with N1,000. By November 2016, we had about N127 million in two accounts, in addition to assets acquired for the budding company.

There will never be a time for a perfect start and it is our fervent hope that the 2019 implementation date for the NDDG will not be pushed forward any longer.

An effective drug distribution system has so many benefits not only for the consumers of the drugs but also for healthcare delivery system and the pharmaceutical industry. We will be able to conserve the scarce resources as the streamlining of drug distribution will promote the implementation of the essential drug to satisfy most of the people. There will be quick and reliable audit trail to maintain the integrity of the system and respond to an intrusion once discovered.

The circulation of fake and adulterated drugs will be curtailed. Drug procurement system will be simplified, with reduced cost and improved efficiency. Generation of data for good health planning is guaranteed. Regulatory task will be facilitated and easier, with an organised system. The Pharmaceutical industry will become more robust. And ultimately, the practice of pharmacy will be enhanced.